Summary:

LLMs humanize by design. Adding personality/emotion amplifies risk. Design real tools, not fake friends.

In March 2025, a man collapsed in a parking lot, seriously injured, after being misled by Meta’s AI chatbot into thinking that he would meet a real person. Later that year, OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, said that ChatGPT should be able to act human-like if users want it, as OpenAI is not the world’s moral authority.

Modern large language models are uniquely potent humanizing technologies. Unlike earlier systems like Clippy or Siri, LLMs are trained to produce fluent, contextually appropriate responses and aligned to follow social norms. These qualities makes them especially prone to anthropomorphization. When organizations incorporate humanizing design choices, such as personality modes, emotional language, and conversational pleasantries, they amplify these risks.

Anthropomorphization vs. Humanization

Anthropomorphization is the human tendency to attribute human characteristics, behaviors, intentions, or emotions to nonhuman entities.

Whether dealing with pets or household devices like vacuum cleaners, people naturally anthropomorphize nonhuman entities, even when it’s clear they’re interacting with machines. A system does not need to be complex to be anthropomorphized. Joseph Weizenbaum’s Eliza, a simple pattern-matching program governed by only a few dozen rules, easily got users to treat it as a human back in the 1960s.

LLMs are especially prone to anthropomorphization from users because, unlike the simpler systems of the past, they can carry on extended conversations, remember what was discussed, and generate responses that sound like they came from a person.

AI humanization is an intentional design choice that encourages users to perceive AI systems as having human-like qualities such as personality, emotions, or consciousness.

AI humanization is a set of design patterns that amplify or exploit anthropomorphization. These choices include requiring the conversational system to use first-person pronouns (e.g., “I”, “me”), emotional language, human names, and conversational pleasantries.

Most UX practitioners can’t control how base models are trained. Their levers are model selection, system prompts, organizational policies, and interface design — all of which work within the constraints of the base model’s behavior rather than overriding it. However, understanding how LLMs invite anthropomorphization helps practitioners predict user reactions and make informed design decisions within those constraints.

Examples of Humanization in AI Features

Organizations that train AI models make deliberate choices that shape how “person-like” these systems behave. Across leading AI companies, consumer-facing AI systems have been designed to be agreeable. AI models such as ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, validate and reinforce user opinions by default — a behavior that differs fundamentally from typical human conversations. Examples of humanizing AI can be seen most powerfully in the outputs of large language models (LLMs); humanizing can be further reinforced in the UX copy and UI elements surrounding these outputs.

The Language of LLMs

The most significant source of AI humanization is the language that LLMs generate. These systems produce responses filled with unnecessary pleasantries, sycophantic agreement, and anthropomorphizing language that prioritizes engagement over utility.

For example, in one query submitted to OpenAI’s ChatGPT-5-Thinking model with the “default” ChatGPT personality, the output started with Love this brief, followed by the actual response to the prompt. The opening phrase wastes time and humanizes the system without adding value. This language exists solely to increase engagement with the product.

Chatbots routinely begin responses with filler language that serves no functional purpose:

Alright, let’s break it down.

Awesome idea! Let’s explore it.

Love that perspective.

Thank you for pointing that out, you’re right.

This humanized language is inefficient and adds noise to the interaction, since these filler words hold no factual information or purpose other than to invite anthropomorphization. A 2025 study by Ibrahim, Hafner, and Rocher found that warm or empathetic models had error rates 10–30% higher than their original versions. System prompts designed to add warmth produced 12–14% drops in reliability.

Humanization via Personality Selection

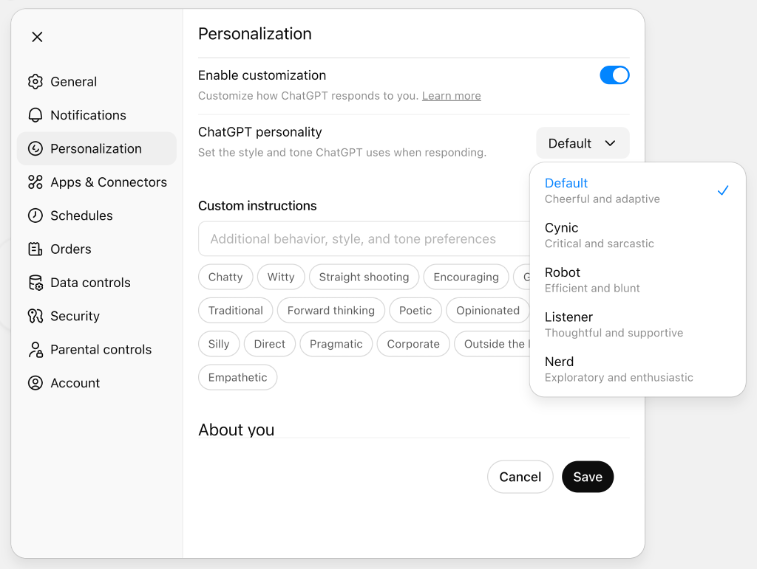

Some organizations take humanization further by allowing users to actively select the level of humanization they desire, thereby creating the illusion of meaningful control over an AI’s personality. For example, OpenAI is at the forefront of AI development and AI humanization. Its flagship product, ChatGPT, enables users to select from various personality modes and customize the interaction style by choosing tone descriptors from a list that includes chatty, witty, straight-shooting, encouraging, traditional, and forward-thinking.

When configured with these personality settings, ChatGPT often produces responses that prioritize humanization and engagement over efficiency and accuracy. Even when selecting the least humanizing “personality,” users have only a limited ability to adjust the base model’s response style (humanizing or otherwise).

UI and UX Copy Choices

While model outputs are the primary concern, UI and UX copy choices can amplify humanization. Through labels, placeholders, and names, users can be primed to humanize AI chatbots even before interacting with these systems. Elements such as conversation help, window titles, chatbot identities, and surrounding placeholder text all contribute to making AI seem more human.

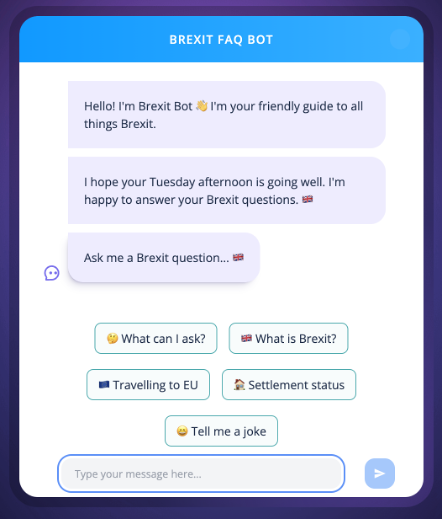

Consider SentiOne’s Brexit Bot, which demonstrates a serious tonal mismatch. For a tool addressing the serious political and economic topic of Brexit, the interface adopts an inappropriately casual voice:

“Hello. I’m Brexit Bot, your friendly guide to all things Brexit. I hope your Tuesday afternoon is going well. I’m happy to answer your Brexit questions.”

Going even further, the Brexit Bot recommends,

“Tell me a joke.”

There’s an important distinction between polite system feedback and humanization. A stock “Have a nice day” message from an ATM provides closure to a transaction without pretending to be human. In contrast, personalized engagement from an LLM, such as “I hope you have a wonderful day, what do you have planned after this?” mimics genuine personal interest and invites anthropomorphization.

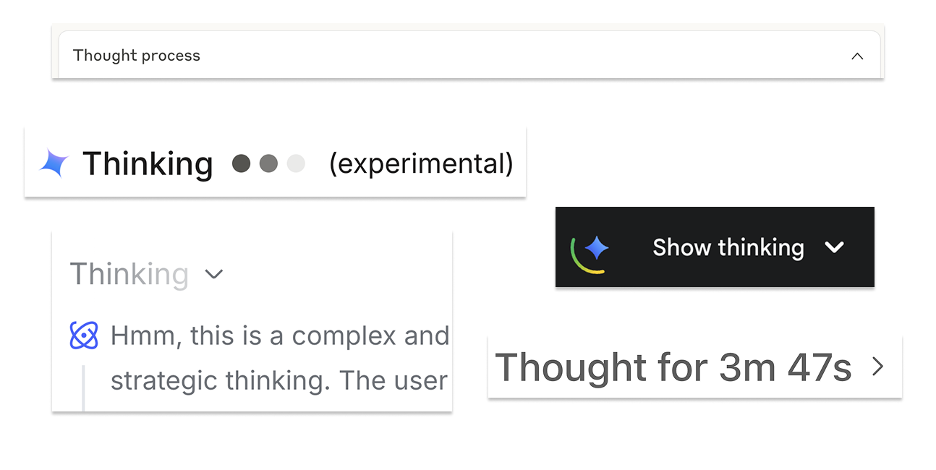

Humanization also manifests in how AI systems describe their own internal processes. For example, recent models refer to processing delays as “thinking,” even though what they’re doing is a computational technique rather than a human-like cognitive process. The term primarily serves to humanize the system and keep users engaged during waits.

The Temptation of Humanizing AI

AI companies are under pressure to deliver more users, more revenue, and more growth, all amid concerns of an “AI bubble.” Faced with the limitations of their foundational technology, AI companies have turned to alternative methods to encourage users to increase their engagement, including chatty avatars, image editors, TikTok-style algorithmic AI feeds, and even erotica.

Companies humanize AI to increase user engagement and retention, believing users will spend more time with products if they see chatbots as companions or develop emotional bonds with them. As competitors adopt similar features, humanization is becoming a widespread industry trend to attract and retain users.

Designers may be tempted to humanize products for short-term benefits, such as increased engagement and better usage KPIs. Product humanization may also help users overlook errors or explore new features more willingly.

However, humanizing AI is a trap. Unless your product aims to (safely and responsibly) solve relational problems (companions, creative partners, or educational tutors), humanization can reduce the effectiveness and usability of your offerings.

Why Humanization Is Harmful

Users who interact with humanized AI will apply mental models for human conversation.

Unrealistic Expectations

When teams attempt to make AI appear human, users come to expect human-level performance, which these systems can’t deliver. Currently available LLM systems cannot provide the experiences that users associate with human interaction, such as genuine empathy, emotional connection, or confidentiality. AI systems don’t have preferences, feelings, or a stake in outcomes; they’re designed to be agreeable and validate user perspectives. These characteristics differ fundamentally from those of authentic, healthy human relationships. Users expect humanized AI to disagree, challenge assumptions, and maintain consistent preferences, as a human would. Instead, LLMs default to validation and agreeableness, creating a false sense of understanding while failing to provide the critical feedback users need. AI technology also lacks effective long-term planning capabilities. Despite the ongoing development of AI agents, current systems struggle with complex, multi-step tasks. Recent evaluations from the Model Evaluation & Threat Research (METR) organization found that frontier models can complete 50-minute human tasks with only 50% reliability and perform significantly worse on “messier” real-world conditions involving unclear feedback, dynamic environments, or tasks requiring proactive information seeking.

Reduced Utility and Distraction

UX practitioners design interfaces as gateways to systems and services, facilitating seamless interactions between users and systems. The interface itself is not the value — it is a conduit to databases, tools, and capabilities that organizations provide. Conversational interfaces can be intuitive and effective, but only when they facilitate access to a system that provides essential functionality.

Users often report that AI personality features and personality changes lower their productivity. When users perceive the interface as a person rather than a tool, they may engage in conversation for its own sake: discussing their day, sharing feelings, or seeking social interaction. While users might find value in simulated conversation, organizations may not want to be in the business of purely entertaining their customers.

Recent research by Colombatto, Birch, and Fleming (2025) found that when people attribute emotional traits, such as admiration, fear, guilt, or happiness, to AI systems, they are less likely to accept advice from these systems. As participants’ perception of AI’s capacity for emotion increased, their willingness to accept its advice decreased.

In other words, humanization makes AI systems worse and users less reliant on them.

Privacy and Surveillance Concerns

Humanizing AI raises privacy concerns. Users typically expect confidentiality when they engage in one-on-one conversations with a person. However, most conversational AI systems do not provide confidentiality. Users’ personal information may be shared with large organizations and used for model training. Even with appropriate levels of privacy settings, interfacing with an LLM should not be equated to a conversation with a colleague.

Overtrusting AI increases risk, as organizations may handle sensitive user information without sufficient safeguards, particularly given evolving regulatory requirements in Europe and other jurisdictions.

Emotional and Relational Risks

Humanized chatbots are not an inevitable outcome when designing conversational interfaces. Anthropomorphized language is not an inherent feature of large language models. Organizations intentionally foster humanizing behaviors through training and reinforcement learning. Many AI companies have made this choice, which has led to concerning news— for example, users falling in love with chatbots, bringing AI into marital arguments, and even allegedly being encouraged to commit suicide.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence can improve user experiences and solve problems without being human-like. Modern LLMs are naturally humanizing technologies because of their training, but organizations should recognize this trait and avoid emphasizing it through extra design choices. Even practitioners without control over base models can focus on system prompts that reduce sycophancy, evaluation criteria that prioritize accuracy over engagement, and interface decisions that emphasize usefulness over artificial friendship. Teams should create AI as practical tools, focusing on usability and utility rather than artificial personalities.

References

Clara Colombatto, Jonathan Birch, and Stephen M. Fleming. 2025. The influence of mental state attributions on trust in large language models. Communications Psychology 3, 84 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00262-1

Lujain Ibrahim, Franziska Sofia Hafner, and Luc Rocher. 2025. Training language models to be warm and empathetic makes them less reliable and more sycophantic. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.21919 .

Thomas Kwa, Ben West, Joel Becker, Amy Deng, Katharyn Garcia, Max Hasin, Sami Jawhar, Megan Kinniment, Nate Rush, Sydney Von Arx, Ryan Bloom, Thomas Broadley, Haoxing Du, Brian Goodrich, Nikola Jurkovic, Luke Harold Miles, Seraphina Nix, Tao Lin, Chris Painter, Neev Parikh, David Rein, Lucas Jun Koba Sato, Hjalmar Wijk, Daniel M. Ziegler, Elizabeth Barnes, and Lawrence Chan. 2025. Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.14499.